A quick one for today. The other day I heard an Indonesian Chinese speaker refer to her (paternal) grandparents as “奶奶爷爷”. This immediately struck my ear as strange, as it’s usually said as “爷爷奶奶”. It then got me thinking about how it’s funny that languages tend to have fairly fixed order for what sounds most natural with ‘A and B’ sorts of noun-phrases.

分类存档:Quick tips

Chinese Learner’s Checklist: 10 Things Everybody Gets Wrong

As a Chinese teacher, over the years I’ve come to see that there are particular topics and language points that students seem to have a ‘mental block’ with, to the point now where I can usually predict in advance which particular content will prove to be a stumbling block with most students. In this post, I want to give you a quick checklist of some of those, so you can make sure that you are okay with them.

42 Ways to Say Goodbye

How many ways do you know how to say ‘goodbye’ in Chinese? Chances are you probably only know 再见 and maybe 拜拜~. Let’s spice up your Chinese with some other ways to bid someone farewell:

Tips Miniseries (9/9): Pre-Verbal Objects

Okay, heads up, this is a tricky one. There’s a secret, little-known alternate position for the object in a Chinese sentence. It’s after the subject and before the verb. At the moment, we probably know of the following positions for the object:

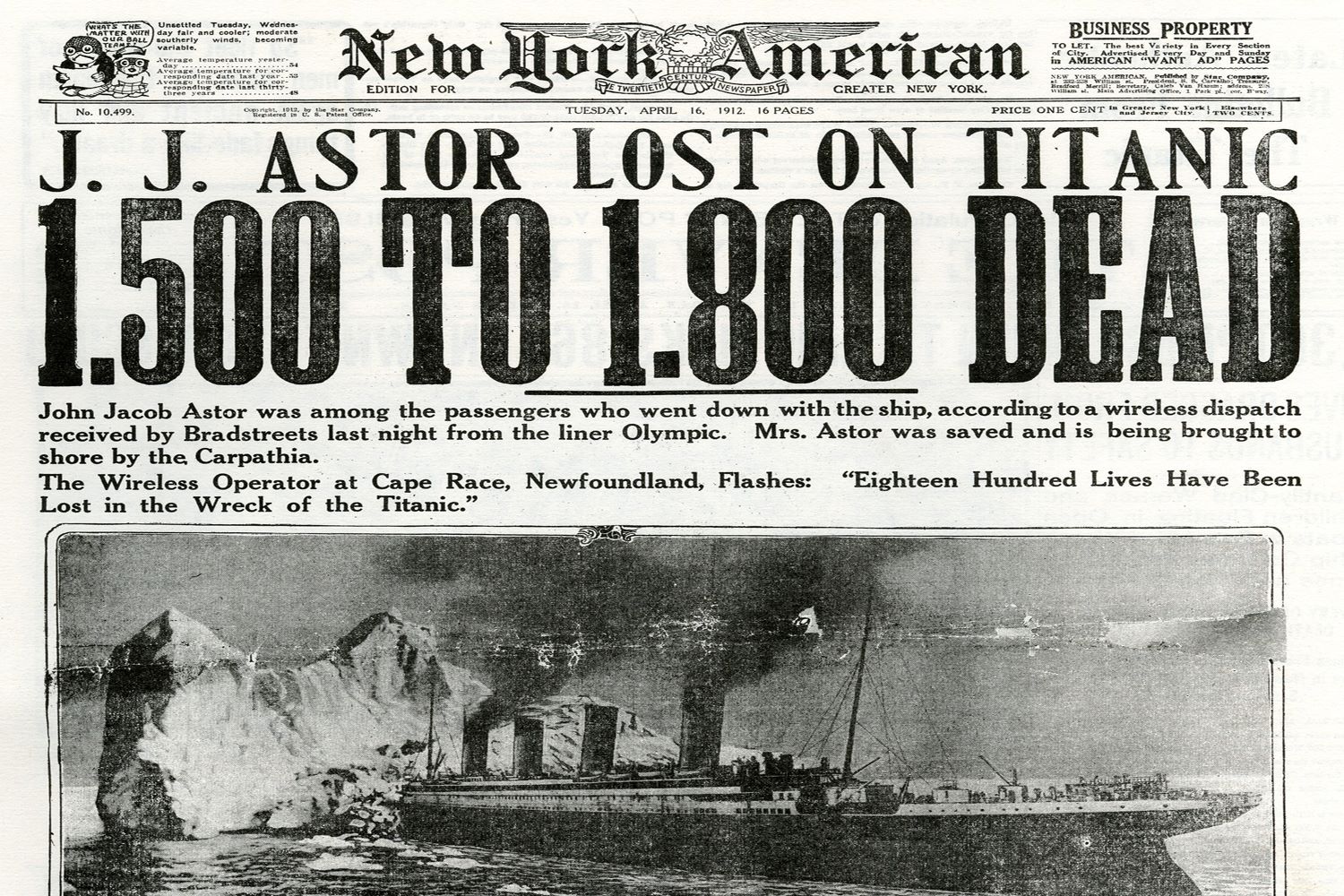

Tips Miniseries (8/9): Duration Structure

I can’t tell you how many times I see students get their duration structure in a pickle – even advanced students seem to get this wrong quite often. By duration structure, I mean when you want to say how long an action was done for e.g. ‘I watched Korean dramas FOR 3 HOURS.’

Tips Miniseries (7/9): Topic-Comment Structure

A distinctly Chinese sentence structure is the TOPIC-COMMENT STRUCTURE. This is a structure that some of you will have heard of, some will have practiced and others will have never heard even once. For those Chinese learners who have heard of it, they nonetheless often avoid using it, because it is one of those structures that seems fairly unusual relative to how we phrase our thoughts as English-speakers.

Tips Miniseries (6/9): Slashing the ‘是’

In the same way that English-speaking students often use too many repeated pronouns in their Chinese sentences (see back to tip #4), which makes their Chinese sound rather verbose and as if it has been sautéed in a glaze of ‘English’, students also have a marked tendency to often use too many 是 in their sentences.

Tips Miniseries (5/9): Where to put ‘what’

Do you know the rule for where question words like 什么、谁、哪里、怎么 etc. go in the sentence? It’s amazing how far through the Chinese subjects students can get at university and still be quite unaware of how to work out exactly where these question words go. This important rule is, in fact, not even that often stated in textbooks. So, what is this magic rule?

Tips Miniseries (4/9): Keep Your Pronouns to Yourself, Please

As you are probably aware, Chinese very much likes to avoid repetition of information that has already been made clear from the context – particularly pronoun words like 我 I, 你 you and 他 he / 她 she. Many English-speaking students, however, copy their English a little too literally into their Chinese and excessively pepper their sentences with superfluous 我、你、他 and 她s.

Tips Miniseries (3/9): Aspect Marking of the MAIN Verb Only

Chinese aspect-markers like 了、过 and 着 show the temporal relation an event has to the time-period you are talking about. However, unlike tense-marking on English verbs, where we obligatorily mark each verb with the appropriate tense (-ed, -t, -en, -ing etc.), Chinese has a tendency to ONLY put aspect-markers after the MAIN verb of the sentence – regardless of their ‘tense’.