*This is, in my opinion, one of the most important articles on this blog – highly recommended reading!

So whilst Deliveroo is processing my order, I thought it was about time I update. Today’s theme is something that is in part something I’ve noticed myself and also part something that I’ve since seen written about to some degree in academic literature, but not really ever in Chinese learning materials.

Most people learning Chinese would have learnt the ‘adverbs go before the verb’ spiel that we dish out to beginner students. We emphasise it so hard, firstly because so many students simply don’t know what an adverb is (damn you, Australian school system!) and also because the struggle of learning characters and getting tongues around tones really makes the logic of the Chinese word order seem more opaque than it really is. It may in fact surprise you when I say Chinese word order is more logical than English word order. Whilst I already hear you decry “Yeaaaahh, the HELL it is!!!”, I’m going to show you the underlying logic of Chinese word order that is basically true ALL THE TIME.

Okay, so the first principle is the core of everything else I’m going to mention. It’s been called ‘the Principle of Temporal Sequence’ by a guy called James Tai (he’s written a paper on it, and whilst I can’t recommend it highly enough for its clarify, I’ve discovered that students [who usually aren’t linguistics students] still find it a little difficult to process – however, I still firmly believe it’s something where you can learn a lot even by looking at the examples, so here’s a link to it for all those who are keen: http://www.ccunix.ccu.edu.tw/~lngsign/Tai_HY_James_1985a.pdf.

The principle goes something like this: the Chinese sentence is a timeline; everything that happens / is known earlier in time is mentioned earlier in the sentence and everything that happens / is known later in time is mentioned LATER in the sentence. Let me give you a few examples. We’ll start with the following pair, which should be fairly digestible for students of any level.

(1) 我在公园跑步。 ‘I run in the park.’

(2) 我经常在公园跟朋友一起跑步。 ‘I often go for a run in the park with my friends.’

EARLIER —————————————> LATER

Now let’s think about (1) as though the sentence were a timeline. First, the action starts with the speaker – it’s something about their life or their habits etc., so 我 comes first. Then, you need to be in the park before you then go for your run in the park, so it makes sense to say 在公园 first before we then say 跑步 (interestingly, this is why you can sort of think of 在公园 as literally meaning ‘be in / at the park’, rather than being an adverbial phrase).

(2) is more complicated, but still works the same way. I’m telling you about something I do, so 我 comes first. Then I’m telling you about my habit / something I do often, so I need to set up the scope of OFTEN (经常) before I then go on to say what the thing done in that habitual time-frame actually is (it actually is easier to conceptualise what I mean here by thinking in the reverse direction – I go running in the park with my friends, then because I do that many times i.e. often, we need to ‘multiply’ the ‘running in the park with my friends’ by a broader sense of ‘often’). Then, as before, I have to be IN the park next, and specifically, in the park ‘with my friends’ before we can do the running together.

If this sounds confusing (the Deliveroo hasn’t arrived yet, so I may not be making as much sense as I think), let’s try looking at it from another perspective: you can say that ‘my habit’ i.e. the thing that I do OFTEN is PART of my life, though not the only thing – hopefully! And so, ‘I / me’ is the BROADER concept that exists in time first and thus it must come first in the sentence (you could also think of it as ‘I / me’ must be existing before my habit is able to exist). Likewise, ‘the park’ is a component, or PART, of my habit and so must come after ‘OFTEN’. ‘Being with friends’ is, in turn, a PART of the situation of what’s going on in the park, so comes after park. Then finally, the running is part of the set of actions my friends and I might do together in the park, so comes at the end. [If you also wanted to be pedantic, you could in fact also say that you have to be ‘with’ i.e. 跟 your friends, before you can all decide to do something ‘together’ i.e. 一起, so 一起 coming after 跟朋友 also makes sense].

我 > 经常 > 在公园 > 跟朋友一起 > 跑步。

Note that this idea also gives rise to the ‘bigger-to-smaller’ word order when you have multiple words of the same type. For instance, when we have multiple time words in a row, there is a fixed order of the broader / larger / more general unit coming first, before the more specific one. For example, in (3) below, we can’t put the time words in any other order e.g. we could not say 二号三月1999年晚上六点半, nor any other variation. So how does this relate to the ‘timeline’ idea? Well, if you think of it, it has to be 1999 first before it can be March of 1999. Likewise, we have to be in March, before it can be the 2nd of March. Exactly for the same reason, we have to put the part of the day, 晚上, after the day it is and the exact time within the evening after 晚上.

(3) 1999年三月二号晚上六点半

The next pair of examples is aimed more at intermediate-level students, as it uses the 把-structure, which is not usually something learnt until you’ve studied Chinese for a year or so. I’ll keep this brief, though.

(4) 我在教室里把他的书拿走了。 ‘I took away (i.e. stole) his book in the classroom.’

(5) 我把书放在了桌子上。 ‘I put the book on the table.’

Students wonder why the place phrase with 在 comes at the end when they’ve had it drilled into them that 在-phrases go BEFORE the verb. The reason is again to do with the ‘timeline’ concept: in (3), I am in the classroom before I then steal the book. In contrasts, in (4) the book ends up ‘on the table’ as a RESULT of the action i.e. I place the book first and then it’s on the table. To paraphrase these examples, (3) means ‘I was in the classroom and then got his book and took it away’ and (4) means ‘I got the book and put it so that it was on the table’.

If you’re curious about what would happen if we still did put ‘在桌子’ before the verb, we’d have an example similar to the following. Whilst this isn’t great Chinese, you can get a meaning from it of ‘I was (standing) on the table and THEN put the book back’.

(6) ?我在桌子上把书放回去。 ‘I stood on the table to put the book back.’

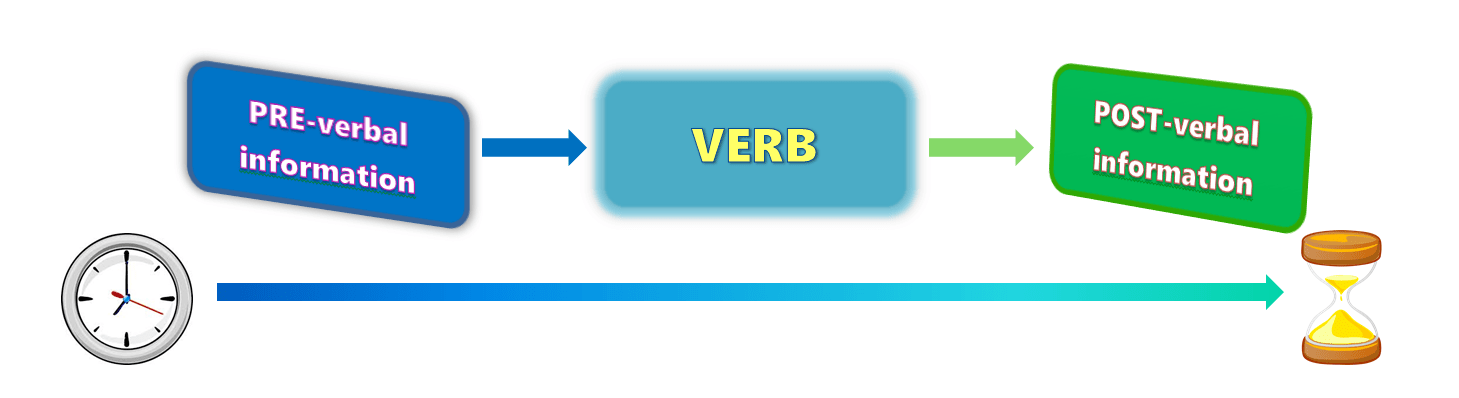

What you may have realised is, the words we are putting before the verb are words / phrases that define the SETTING of the action – when it takes place, where it takes place, with whom it takes place etc. This is because the verb is actually a pivotal point within the Chinese ‘timeline-like’ sentence. Information that comes before the verb is known or true prior to the action of the verb being started. Information that comes after the verb is only known once the action is either underway or completed – that is, it shows the RESULT of the action.

EARLIER ——————————————–> LATER

BEFORE VERB VERB AFTER VERB

setting, known / true first action result, known / true after action starts

The clearest example of this pre-verbal / post-verbal distinction is with adverbs. Below, I’ll give you some clear examples of different types of adverbs and the difference in meaning that results from their pre-verbal and post-verbal placement.

(7) ADVERBS OF TIME

(a) Pre-verbal

(i) Time ‘when’

我们明天见个面吧。

‘Let’s meet tomorrow.’

(ii) Time-frame within which the action is to be done

游戏规则是要在一个小时内把所有的东西都吃完了。

‘The rules of the game are that you have to eat everything within an hour.’

(iii) Time NOT doing

我们很久没见面了。

‘We haven’t met for a long time.’

(b) Post-verbal

(i) Duration

我昨天看电视看了一个半小时。

‘I watched an hour and a half of TV yesterday.’

(ii) Time the action will continue until

我这么累了,估计可以睡到后天。

‘I’m so tired. I reckon I’ll be able to sleep until the day after tomorrow.’

(8) ADVERBS OF FREQUENCY

(a) Pre-verbal

(i) The number of times the action HASN’T happened

我三次都没见着他。

‘I didn’t see him any of those 3 times.’

(ii) Ordinal frequency i.e. ‘the nth time’

我第一次见到她就一见钟情了。

‘The first time I saw her, I fell in love with her (at first sight).’

(b) Post-verbal

(i) The number of times the action happens

我们见过三次面了。

‘We’ve met three times now.’

(9) ADVERBS OF PLACE

(a) Pre-verbal

(i) The place where the action takes place

同学们都在家里休息。

‘Our classmates are all resting at home.’

(ii) Intended destination / direction set out

我明年要到北京去学习汉语。

‘I want to go to Beijing next year to study Chinese.’

(iii) The source where someone / something comes from

他是从中国来的。

‘He came / has come from China.’

(b) Post-verbal

(i) Actual destination

电脑放(在)那边了。

‘The computer has been put (over) there.’

(ii) Resulting place

他们坐在沙发上聊了一会儿天。

‘They chatted for a while whilst seated (i.e. having sat down) on the sofa.’

(10) ADVERBS OF MANNER

(a) Pre-verbal

(i) The attitude / style with which the action / task is approached

你们要好好学习,以后才能找个好工作。

‘You should study hard so that you can find a good job in the future.’

(ii) What is used to conduct the action

用中文怎么说?

‘How do you say it in (literally: using) Chinese?’

(iii) Who the action is done with

他在跟一个漂亮的女生跳舞。

‘He’s dancing with a pretty girl.’

(b) Post-verbal

(i) How successfully the action is carried out

你唱歌唱得非常好听。

‘You sing really well.’

(ii) How the action makes others feel

你的歌唱得我都要哭了。

‘Your singing made me want to cry / tear up.’

(11) ADVERBS OF DEGREE

(a) Pre-verbal

(i) Ordinary indication of degree

非常好!

‘Excellent!’

很好!

‘That’s great!’

不贵。

‘Inexpensive.’

(b) Post-verbal

(i) Indication of degree with more of an emotive effect / result

今天热死了!

‘It’s boiling hot today (literally: hot to the point of death)!’

这人真是坏透了!

‘This person is horrid through-and-through!’

便宜得很。

‘Very cheap.’

(12) ADVERBS INDICATING THE BENEFICIARY

(a) Pre-verbal

(i) Indicating on whose behalf the action is being carried out

我给你买了个礼物,所以你有东西送了。

‘I bought a gift for you, so now you have something to give.’

(b) Post-verbal

(i) Indicating the recipient of the action

我买了个礼物给你,你肯定会喜欢的。

‘I bought a gift for (i.e. to give to) you. You’re definitely going to love it.’

Alright, today’s post was an abstract one – abstract, but crucial! I’d be very happy to answer any questions about this in the comments below. Also, do check out the Tai paper that I linked you to above.

88 for now!!