Everyone loves the 把-structure….don’t they?? *silence*. Oh well, it’s actually pretty useful! It’s one of THE biggest sources of confusion for students learning Chinese, so I wanted to take the time to do a fairly thorough post that (hopefully) demystifies what 把 is all about. We’ll talk about what the 把-structure is, why it’s used and how it’s formed. I’ll then be giving you some tips and examples on how to know when to use it. [*Note*: several of the examples in this post come from The Syntax of Chinese by Huang et al. (2009)]. So without further ado, let’s begin! There’s no need for 把 to send you 把-my, its 把-rk is worse than its bite!

1. WHAT IS 把?

The exact nature of what type of word 把 is has been a subject of controversy and debate in Chinese linguistics for quite some time – 把 is actually one of the most enduring topics discussed by researchers even today!

The main thing to understand about the ‘word type’ of 把 is that grammatically, it fills the same slot in the Chinese sentence that prepositions like跟、对、往 and 给 fill. In the same way that prepositions are usually followed by nouns, 把 takes a noun-phrase immediately after it (which in actual fact originates as the object of the verb and then moves to the pre-verbal, post-把 position – more on this shortly).

Virtually all prepositions in Chinese either originally started out as verbs in their previous life, or still have verbal uses – you may note, for instance, that 给, as well as being the preposition ‘for, on behalf of, for someone’s benefit’ also can be a verb meaning ‘to give’. 把 is no exception here – it started out in its previous incarnation as an ordinary verb meaning ‘to grab, to grasp’, its verbal meaning still evident in words like 把握 ‘to have a grasp of something’、把弄 ‘to play around with’ and 门把 ménbà ‘doorknob, door handle’ (where in older forms of Chinese, tone change was sometimes used to turn a verb into a noun). As with other prepositions, we say that the verbal meaning of 把 has now become ‘grammaticalised’ – that is, it has developed a special, more ubiquitous grammatical purpose that relates to, but extends beyond its original meaning.

Like all other prepositions, 把 cannot take aspect marker suffixes e.g. **把了、**把过、**把着 [*note*: I used ** to indicate ill-formed/ungrammatical/incorrect examples]. And typical for prepositions, we can’t use 把 in the A不A structure to make a question i.e. **把不把. Finally, we can’t use 把 to answer a question that was phrased using the 把-structure eg.

A: 你把作业做完了吗? ‘Did you get the homework done?’

B: **把。 ‘Yes.’ / **不把。 ‘No.’.

Instead, it should be:

B: 做完了。 ‘Yes.’ / 还没。 ‘Not yet.’

For a bunch of technical reasons, the ‘a bit like a verb, but a bit like a preposition’ status of 把 has led researchers recently to classify 把 as a ‘light verb’. I’m not going to explain what that means, as it’s super technical and probably doesn’t add much to our discussion here, but just be aware that this is suggesting to us that 把 behaves a little atypically overall when compared to other word classes, though in many ways, also does have a lot of properties in common with verbs and with prepositions too.

2. FORMING THE 把-STRUCTURE: WORD ORDER

Before we get into discussing WHY one would want to use the 把-structure ever, let’s start off with the basic word order facts and how to form the structure. A 把-structure is formed essentially by doing 2 things:

- moving the direct object from its post-verbal position to the pre-verbal position after 把

- adding some extra information after the verb (sometimes called a ‘complement’ – though in pure linguistic terminology, this term is actually problematic)

The word order pattern is thus:

subject + (adverbs) + 把 + object + (some adverbs) + verb + complement

e.g. 他把水喝完了。 ‘He finished drinking the water.’

e.g. 妈妈把桌子擦干净了。 ‘Mum wiped the table clean.’

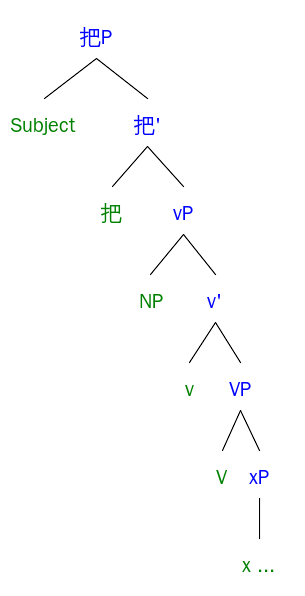

( For those of you who want the technical linguistics syntactic tree structure, here it is below. If you’re not familiar with this level of technical analysis, don’t worry, it’s helpful, but not essential to understanding anything in the remainder of this post. [Note: unlike with 被, no operator movement is involved. Note also the standard use of abbreviations: NP: noun-phrase, V: verb, VP: verb-phrase, vP: outer verb-phrase shell (voice-phrase), v: head of voice-phrase, xP: any phrase-type, x: head of xP] )

(Don’t fret if this doesn’t make sense to you – it ‘s only for the readers who know about this stuff.)

For those who are following the tree diagram above, an interesting observation is that rather than having the structure:

[[把 NP] V]

we actually have the structure:

[把 [NP VP]]

with the post-把 noun-phrase and the verb-phrase forming a constituent, the noun-phrase essentially being a kind of ‘secondary’ subject of the internal verb-phrase.

The relevance of this fact will become apparent later, but something useful for all readers to note is that, although not extremely common, we can actually have more than one action after 把, each with its own ‘subject’, joining them with a comma. These kinds of examples can be thought of as a short-hand way of joining two 把-sentences together on-the-fly e.g.

他把[门洗好],[窗擦干净]了。

‘He washed the door and wiped clean the windows.’

Short for: 他把门洗好了 AND 他把窗擦干净了。

你把[这块肉切切],[那些菜洗洗]吧!

‘Cut this piece of meat and clean those vegetables!’

Short for: 你把这块肉切切吧 AND 你把那些菜洗洗吧。

If you have adverbs you wish to add to the sentence:

- they usually go before 把

e.g. 他一下子把水喝完了。 ‘He finished drinking the water in one fell swoop / in one go.’

e.g. 林一在把衣服包成一大包。 ‘Linyi is putting his clothes into a bundle.

- manner adverbs are an exception and can go either before 把 or before the verb

e.g. 他赶紧把水喝完了。‘He finished the water quickly.’

OR 他把水赶紧喝完了。 ‘He finished the water quickly.’

- I read somewhere that adverb 都 always goes before 把, but I have some doubts that this is always true and in fact think that the position of 都 can change whether or not the 都 is referring to the subject or the object:

e.g. 他们都把水喝完了。 ‘They all (i.e. every one of ‘them’) finished drinking their water.’

e.g. 他们把水都喝完了。 ‘They finished (between them) all of the water (i.e. all of the ‘water’).’

One common mistake that students make with 把 is that they move the object to the ‘after-把, before-verb’ position, but then forget to take the object out from its original position after the verb, their sentences often ending up with the same object stated twice (in linguistics, we call this a ‘resumptive pronoun’, and in some languages, it’s a legitimate thing, but for the 把-structure, NO, NO, NO!).

** 他把作业[correct position]做完了作业[original, redundant position]。 Intended: ‘He finished his homework.’ Actual: **‘He finished his homework the homework.’

A fairly rare word order inversion that happens sometimes (only) in colloquial speech is that the 把 and its object can be preposed/topicalised to the front of the sentence to emphasise the ‘doing of something to that object’ [though note that this is disallowed when using ‘causative 把’ – see section 5 > ‘Reason #3’]. You may never even hear this ‘inverted 把-structure’, but it’s always good to know more ways in which Chinese speakers might express themselves. A couple of examples are given below for your reference (for those who followed the technical, linguistic detour just before, it might occur to you that this preposing of ‘把 + object’ implies the structure [[把 NP] VP], rather than the [把 [NP VP]] which we just claimed. My answer to this is…*shrugs*…):

e.g. 把那堆文章,我早就改好了。

e.g. 把这块肉,你先切切吧!

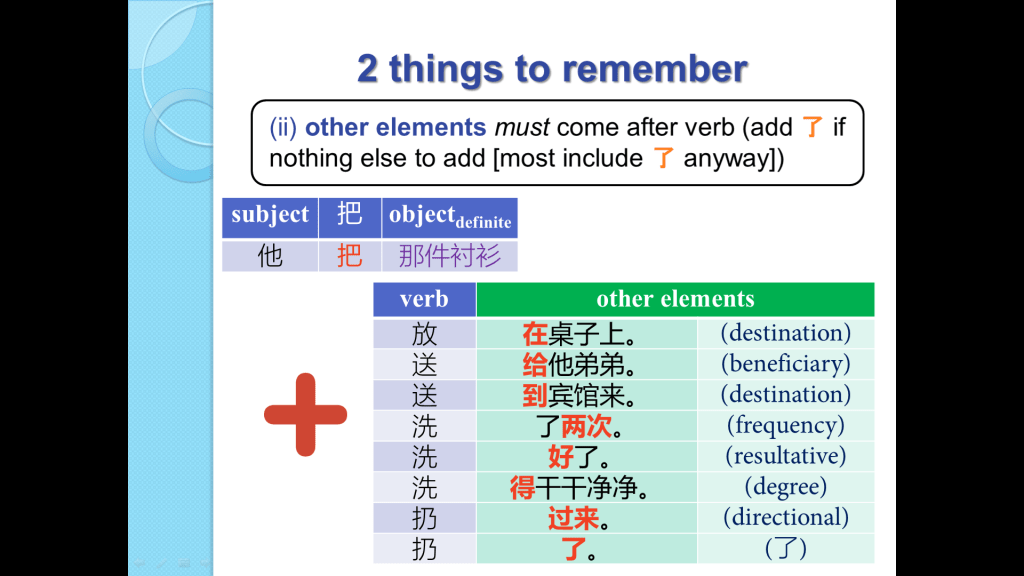

You might notice that in all of the above examples of the 把-structure, we never ended the sentence with just the verb hanging by itself. In all cases, we had something after the verb filling the ‘complement’ position in the word order pattern. We’re going to talk about what elements can fill this ‘complement’ position in a second, but for now, the main thing to remember is that as well as the word order pattern above, there are 2 key requirements that must be adhered to when using the 把-structure:

- the object must be definite

- there must be some extra information acting as the ‘complement’ after the verb

Let’s now look at each of these in turn.

3. CONSTRAINT #1: THE OBJECT MUST BE DEFINITE

In the 把-structure, the object of the ‘original’, non-把 version of the sentence moves from its post-verbal position to after 把. In some ways, you can think of 把 as having its original meaning of ‘to grasp, to grab’ and it still makes sense as a mere sequence of verbs e.g.

小偷把我的书包偷走了。 ‘The thief stole my backpack.’ More literally: ‘The thief grabbed my backpack and stole it.’ Slightly less literally: ‘The thief took/got my backpack and stole it.’

Because of the high sense of focus on the object, the object noun-phrase that comes directly after the 把 must be what we refer to as ‘definite’. Roughly speaking, what this means is that it must clearly refer to a particular or specific object, or group thereof. As such, when using the 把-structure, the object rarely is preceded by vague (indefinite) specifications like ‘一个’ ‘one’, but is much more commonly preceded by determiners such as ‘这 + measure word’ ‘this’ and ‘那 + measure word’ ‘that’ that indicate specificity. Possessive words like ‘我的’ and proper nouns also work well to show specificity. Interestingly, an unmarked, ‘bare’ (naked) noun by itself is fine, so long as it can be interpreted in the context as referring to 1 or more particular individuals/items (usually this means they will the item(s), rather than some items or a(n) item. Numbers other than ‘一个’ can go either way, depending upon the context, but in most cases tend to feel a little bit too non-specific to work with 把. Here are some examples showing what I mean:

**他把一封信放在桌子上。 ‘He put a letter on the table.’ [一封 is too vague]

他把那封信放在桌子上。 ‘He put that letter on the table.’ [那封 is much more specific]

他把我的信放在桌子上。 ‘He put my letter on the table.’ [我的 is specific]

他把信放在桌子上。 ‘He put the letter(s) on the table.’ [works if we assume that a particular letter / particular letters are currently being discussed in the context]

**他把六封信放在桌子上。 ‘He put six letters on the table.’ [六封 is too vague – which six? It could be any six letters!]

他把六封信放在桌子上。 ‘He put the six letters on the table.’ [六封 is okay iff we have 6 particular letters under discussion in the context]

Just to mess with your brain, I’m going to give you an example where ‘一个’ before the object can work with the 把-structure, the reason being that in this particular example, there’s a clear sense of exactly which 机会 ‘opportunity’ is being referred to. What I’m attempting to illustrate by showing you this example is that this idea of the ‘definiteness’ of the object is about contextual meaning more than it is about there being ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ words to use with the 把-structure:

他把一个美好的机会错过了。 ‘He missed such a (/that) great opportunity.’

Interestingly (though I wouldn’t blame you if you weren’t the slightest bit interested by this), the inanimate 3rd-person singular pronoun 它 ‘it’, which is seldom used in Chinese normally, often shows up in the 把-structure. If you think about it, we very rarely use 它 in Chinese, compared to ‘it’ in English e.g.

A: 你喜欢吗? ‘Do you like it?’ [we very rarely say 你喜欢它吗?]

B: 我很喜欢。 ‘I like it a lot.’ [we very rarely say 我喜欢它。]

In the 把-structure, however, 它 makes a comeback and proves its worthy of being spared total deletion from the lexicon by being a generic way to indicate that the speaker is in fact referring to a particular object of some kind. For instance [note that these sentences wouldn’t work without 它 present, as there would be no object going with the 把 – just like a Tinder date without the love – oh wait, that’s just a Tinder date…]:

A: 你把它怎么样?

‘What did you do to/with it?’

B: 我把它扔掉了。

‘I threw it away.’

你怎么把它弄丢了呢? ‘How did you manage to lose it?’

Whilst usually not mentioned in learning resources, usually the subject of a 把-sentence is definite also. The following example clarifies these points [note the use of a single * to show ‘it’s a bit weird, but perhaps not outright wrong’]:

我们昨天把电脑弄坏了。

*大家昨天把电脑弄坏了。

*每个人昨天把电脑弄坏了。

4. CONSTRAINT #2: MORE DEETS, PLS

Ever been sent a Facebook event invite only to discover the time and the date are not included in the details? Well, that’s what you get if you use a 把-structure without a complement! Everything we’ve said about the 把-structure so far has been geared towards it referring to specific situations – the object, the subject are all specific. So, naturally, we have to show in the sentence that the action the subject and object have entered into is also a specific one. This burden is undertaken by the post-verbal ‘complement’ position, a slot which has to contain some sort of information that elucidates how the action/state expressed by the verb is a specific instance (or set of specific instances). There’s quite a bit of versatility in terms of what can come in the ‘complement’ slot, so hear is a (fairly) comprehensive list of options, all illustrated on the same core sentence:

Here’re some more details on each of the possible options for the ‘complement’ slot:

(a) destination place

e.g. 他把书放在了桌子上。 ‘He put the book on the table.’

Note that we normally think of ‘place phrases’ as going before the verb e.g. in the sentence 我在家里说汉语 ‘I speak Chinese at home’, the place where the action happens, ‘在家里’ goes before the verb 说. If you like, we could say that this pre-verbal position is for place phrases that indicate the setting in which the action takes place. With ‘place after the verb’, however, the place is where the action finishes. In the example above, ‘桌子上’ ‘on the table’ is the resulting place of where the book object ends up, not the place where the subject ‘他’ does the ‘placing’ of the book. If you are curious about what the above example would indicate if we did put the place before the verb, we’d get something like:

他在桌子上把书放了。 ≈ ‘He was on top of the table and then put a book down (probably also on the table)’.

Another thing that might have caught you out with the example above is the appearance of 了 after the 在 – something that seems a little ‘off’ grammatically. Whilst we might think that because 放 is the verb and 在桌子上 is the place phrase, 了 should come after the 放, with ‘destination place’ phrases, the 了 comes after the verb + its suffix i.e. 放在了、放到了、交给了. As you can see, this fact is not just true when the suffix is 在, but also when it is another preposition like 到 or 给.

(b) beneficiary (who ended up with something as a result of the action)

e.g. 他把书送给了弟弟。 ‘He gave the book to his younger brother’.

The ‘complement’ can be 给 in its prepositional form meaning ‘for’, showing who ends up receiving the object once the action is through. As with 在 in (a), note that the 了 comes after the verb + 给, rather than between the verb and 给.

(c) duration

e.g. 他把鞋子擦了几分钟。 ‘He scrubbed his shoes for a few minutes.’

Even simply saying how long the action lasted can be sufficient to fill the ‘complement’ slot.

(d) frequency

e.g. 他把弟弟打了三下。 ‘He hit his little brother 3 times.’

Does pretty much what it says on the tin 😉 Simply says the number of times the action was performed.

(e) result(ative verb) complement (RVC/RC)

e.g. 他把作业都做完了。 ‘He finished all of his homework.’

This is another fairly straightforward case – often the choice of RVC will be one that indicates volitional and deliberate completion e.g. ~完 to show finishing of a task, ~好 to show preparing or making something ready or ~光 to show performing the action until nothing is left.

Note that either subject or the object can be the one experience the result state indicated by the RVC, depending upon context e.g.

小孩子把妈妈追累了。 ① ‘The kid chased his mum until he was tired.’ or ② ‘The kid chased mum until she (i.e. mum) was tired.’

(f) directional complement

e.g. 他把书放回去了。 ‘He put the book back (where it was supposed to go).’

This is just a sub-type of RVC that shows the direction in which the action resolves. You can check out the dedicated post about RVCs for more information about this type of complement.

(g) complement of degree (得)

e.g. 他把书看得非常仔细。 ‘He read the book very carefully.’

Adding a description that shows how the action unfolded is sufficient material to fill our ‘complement’ slot in the 把-structure. Options (d), (e) and (f) all show that the ‘complement’ slot need be filled by some sort of elements that show how the action unfolds or results. Elucidation on the specific-ness of the action, as we mentioned earlier, is the name of the game here.

(h) reduplicated verb

e.g. 你把那些菜洗一洗吧。 ‘Give those vegetables a clean.’

Even just doubling the verb (where appropriate) to show suggestion, or non-committal undertaking of an action is sufficient to fill the ‘complement’ slot.

(i) aspect marker (了、着 etc.)

e.g. 他把书拿了。 ‘He took the book.’

If you really can’t think of any extra information you want to add to your 把-sentence in the ‘complement’ slot, you can just put a 了 on the end and hope for the best. 70-80% of the time you’ll get away with it, even if the sentence does sound a little bit brief, abrupt, ‘vague’ or ‘incomplete’. This ‘bare minimum’ addition of 了 occurs 6-7% of the time in a corpus search done by our friends Li & Thompson (1981), so it’s definitely a possibility you can consider.

Note that although 了 is the most common ‘bare minimum complement’ used with the 把-structure, other aspect markers like 着 can potentially take on the same role e.g.

他把书拿着。 ‘He picked up (and continued holding) the book.’

(j) a note on 所

For the more advanced students among you, you may be familiar with a sentence pattern where the classical particle 所 is used before the verb e.g.

我很感激你为我所带来的幸福。 ‘I am thankful for the happiness you have brought me.’

Just be aware that the use of particle 所 in this way is not permitted with the 把-structure:

** 我把它所弄坏了。 ‘I broke it.’

5. WHY USE THE 把-STRUCTURE ANYWAY?

Alrighty! Now that we have seen how the 把-structure works and how it is put together, it is time for THE over-arching question that is on most students’ minds – WHY and WHEN should one use the 把-structure in the first place?

The answer to this question becomes even more confusing when we note that researchers in Chinese linguistics postulate that every 把-sentence has a non-把 counterpart sentence (note that this does not mean that every sentence has a valid 把 equivalent) – in other words, there is technically no 把-sentence that could not be expressed in some other way, a fact which can make the reason for its existence even more circumspect. Rest assured, however, that there are cases where using 把 clearly is the most natural option, and the 把-structure has several very handy uses – both semantically and syntactically. What’s more, often the non-把 version of particular sentences becomes so wordy and awkward that 把 is almost definitely called for to save an otherwise train-wreck of a sentence. So let’s look at why the 把-structure is useful and what it adds meaning-wise and nuance-wise that wouldn’t otherwise be expressed by a non-把 equivalent.

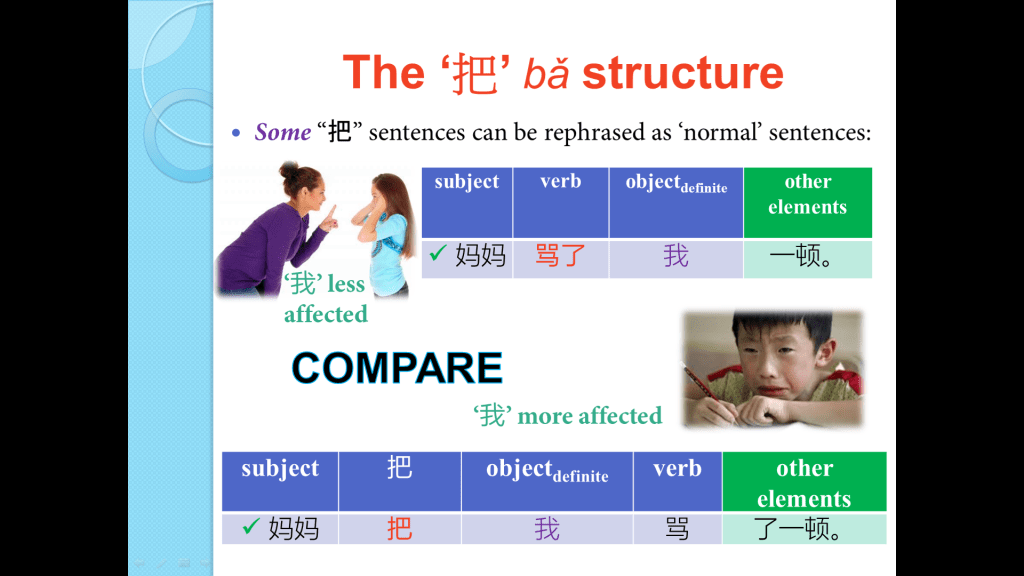

>> Reason #1: Showing the object is ‘affected’ or ‘changed’

Usually, the 把-structure shows that the object noun-phrase that comes after the 把 is changed in some way by the process of the verb. As such, linguists often like to call it the “affected object”. The change in the object could be e.g. it is broken, it is moved to another location, it is split up into parts, it is given away, its state is changed, it is affected in some non-trivial way etc. You may like to think of the object moving closer to the front of the sentence in the 把-structure as symbolic of the把-structure focusing on the change in the object.

Because of this dynamic sense of the subject affecting a change in the object, it is only natural that the把-structure very often be found with action verbs and in particular, verbs of physical movement e.g. 搬 ‘to move’, 放 ‘to place’, 送 ‘to send over’, 打 ‘to hit’, 偷 ‘to steal’ etc. Conversely, the 把-structure sounds weird with verbs that don’t actually change the object in some way. As a good rule of thumb, you can remember that the 把-structure generally does NOT go well with the following types of verbs:

The verb cannot be a state or classificatory verb:

**喜欢、**认识、**是、**有

e.g. **我把她认识了。

Unless the degree of the state is so high/exaggerated (usually in some non-physical or imaginary situation) that it creates a sense of ‘someone/something being affected’ – though note in these cases, it is in fact the subject who is feeling the effects here, not the object (Li & Thompson, 1981):

e.g. 他把你想得饭都不肯吃。

e.g. 他把小猫爱得要死。

See how this doesn’t work so well when the verb isn’t very exaggerated:

e.g. 我会把他恨一辈子。 [恨 ‘to hate’ is very strong/exaggerative]

e.g. 他一定会把你恨透的。 [恨 ‘to hate’ is very strong/exaggerative]

e.g. **我会把他怕一辈子。 [怕 ‘to fear’ isn’t strong/exaggerative]

e.g. 小孩把他想得要死。 [想得要死 ‘to miss to death’ is strong and exaggerated]

e.g. **小孩把他像得要死。 [in 像得要死 ‘to be similar to death’, the verb ‘像’ ‘to resemble/be similar to’ simply isn’t strong enough to allow the use of 把; the sentence makes sense without 把 though i.e. 小孩像他像得要死。]

The verb cannot be a verb of perception:

**看到、**听见、**发现、**知道

e.g. **我把她看到了。

Nor can it be an action that doesn’t really ‘do’ something to the object:

**我们把他拜访了很多次。

Sometimes the ‘change’ in the object is more true in an abstract sense than any real, physical sense e.g. in the following example, the ‘机会’ has not really been affected by ‘他’ missing it, but it has been affected in a more abstract sense in that it is now classified as a ‘missed opportunity’, whereas before it was simply a ‘(potential) opportunity’:

他把一个大好机会错过了。 (Liu, 1997)

The next logical thing to ask is, given that one is using a verb that is basically compatible with the 把-structure, what would be the main difference between a 把-sentence and its non-把 equivalent? Let’s look at the following example to explore this:

Although the core meaning of what action is taking place is the same in both sentences, the 把-structure version has much more of a heightened sense of ‘我’ being “affected” by mum telling them off. At the very least, one would imagine ‘我’ is significantly more upset and/or shaken by the 把-structure telling off than the non-把-structure telling off!

>> Reason #2: An extra ‘slot’ in the sentence structure

Whilst reason #1 for using the 把-structure was to do with meaning, there is also a syntactic (i.e. grammatical) benefit for using the 把-structure. In most cases, we think of an ordinary sentence as having 2 noun-phrase ‘slots’ – the subject slot and the object slot i.e. someone/something [=slot 1] does an action to someone/something else [=slot 2] (in linguistics terminology, we call these ‘slots’ ‘theta-roles’/‘θ-roles’). Adding 把 to the sentence, as is true of prepositions generally, creates an extra ‘slot’ in the sentence to mention a third, additional noun-phrase participating in the event. Because in the 把-structure, the direct object moves to the pre-verbal position after the 把 (making 把 a little more atypical of prepositions), this means that the extra position for the third event participant is in fact the old, now-vacated object position after the verb, which makes it feel very natural to phrase rather complicated events, such as someone/something [=slot 1] does an action to the someone/something else [=slot 2] which is (of) someone/something else [=slot 3].

This is all getting rather technical, so let’s look at some examples and you will see what I mean. To show students the value of this ‘extra slot’ that 把 creates in the sentence, I often give the example of trying to phrase in Chinese ‘I translated the book into Chinese’. Give this a try before reading on (you may like to know that the verb ‘to translate’ is 翻译 fānyì) – you’ll find that without using 把, it’s actually quite difficult! And most likely, you’ll find it’s difficult because you keep getting this feeling of ‘there aren’t enough slots in the sentence to put all the words I need to include’. Here’s a few attempts at phrasing this without 把 before giving you the (much more straightforward) 把-version.

*那本书,我翻译成中文了。 [ok, but feels a bit like child-speak]

*我那本书翻译成中文了。 [ok, but entails that the book belongs to ‘我’]

**我翻译那本书成中文了。 [RVC 成 ‘into’ needs to come directly after the verb 翻译]

**我翻译成中文那本书了。 [sounds odd to me] The ‘good’ version: 我[=slot 1]把那本书[=slot 2]翻译成中文[=slot 3]了。 [:-) and they all lived happily ever after…]

In fact, all cases where we have a third event participant become significantly hard to phrase in Chinese without the 把-structure, yet are made short work of when we do use 把. These include:

A verbs B in/at place C e.g. 他[=slot 1]把照片[=slot 2]放在桌子上[=slot 3]。

A verbs B to place/person C e.g. 他[=slot 1]把照片[=slot 2]送给他弟弟[=slot 3]。 e.g. 他[=slot 1]把照片[=slot 2]送到宾馆来[=slot 3]。 e.g. 我[=slot 1]想给你[=slot 2]介绍我的朋友们[=slot 3]。 ➙ 我[=slot 1]想把你[=slot 2]介绍给我的朋友们[=slot 3]。 [ok without 把, smoother with 把]

A verbs B into C e.g. 我[=slot 1]要把那本书[=slot 2]翻译成英文[=slot 3]了。

A verbs B onto C 他[=slot 1]把名字[=slot 2]写在了信封上[=slot 3]。

These kinds of language structures are often called ‘dative’ structures, and with the addition of other verbs, it’s possible to get even more than 3 event participants involved:

e.g. 老板[=slot 1]要求我们[=slot 2]把所有WORD文件[=slot 3]转换为PDF[=slot 4]。

A consequence of 把 creating an ‘extra noun-phrase slot’ is that it can be used in a slightly varied way that is not really ever taught to students in any learning resources. In the examples below, note how the main ‘affected object’ is moved to the pre-verbal, post-把 position, but there is in fact still an object that exists in the usual post-verbal position at the same time. This seems strange, as wasn’t the whole point of the 把-structure that we move the object out from its post-verbal position to a pre-verbal one? Well, it may help to realise that in cases like this where we have the 把-structure PLUS a post-verbal object, the post-verbal object is usually in some kind of possessive or part-whole relationship with the post-把 object. The structure is thus:

subject + (adverbs) + 把 + ‘affected’ object + (some adverbs)

+ verb + part of the ‘affected’ object

And here are some examples:

我要把他打断腿。 ‘I want to break his leg.’ [Literally: ‘What I want to do to him is break his leg.’]

我把林一抢走了帽子。 ‘I took away Linyi’s hat.’ [Literally: ‘I stole-hat from Lisi.’]

A: 你把桔子怎么样了?

‘What did you do with/to the tangerines?’

[Literally: ‘You took the tangerines and did what (to them)?’]

B: 我把桔子剥了皮了。

‘I removed the skin from the tangerines.’

[Literally: ‘From the tangerines I removed their skin.’]

In examples like the following, I find it useful to think of the sentence as expressing a ‘verb + object’ action that is directed at another entity:

我把卡车装满了稻草。 ‘I filled the truck full with straw.’ [Literally: ‘I filled-full-of-straw the truck.’]

我把李四免了职。 ‘I fired Lisi.’ [Literally: ‘I took-away-job at Lisi.’]

Whilst at first, this use of 把 can be difficult to get your head around, I guarantee you that if you can use this kind of structure occasionally, your Chinese will sound more authentic than about 99% of all other learners out there –I don’t think I’ve ever heard a non-Chinese use the 把-structure in this interesting, yet highly natural and common way!

>> Reason #3: Using 把 to show ‘causative’ meaning

* A note on this section: it starts off a bit technical, but the main information useful to learners comes towards the end.

You may recall that at the start of section #3, I said that 把-sentences broadly make sense of you think of 把 as having its literal meaning as a verb of ‘to grab, to grasp’. However, in the examples at the end of the previous section, you may have begun to feel that seeing 把 in this way stopped making quite as much sense as it did before. For instance, in the example below, it’s not quite right to describe the situation as ‘I grabbed Linyi and took away his hat’ – at no point did ‘我’ grab or grasp Linyi, only his hat!

我把林一抢走了帽子。 ‘I took away Linyi’s hat.’ [Literally: ‘I stole-hat from Lisi.’]

Another way to think about the examples at the end of the previous section is with 把 indicating the meaning of ‘causing’ something to happen/be the case, and the subject being the causer. For instance with the example below, it makes logical sense to see the subject ‘我’ as the causer and the smaller, internal sentence ‘他打断腿’ as being the state of affairs that ‘我’ causes:

我要把他打断腿。 ‘I want to break his leg.’ [Literally: ‘I want to be the cause of a situation where he breaks his leg.’]

This actually makes perfect sense with the technical details discussed in section 2 (I know that I said you could skip them if you weren’t familiar with this type of technical analysis, but I want this account to come ‘full circle’ for those who were following that part). If you recall, in simple terms, we were saying that the 把-structure includes the following 3 parts:

- 把

- noun-phrase

- verb-phrase (made up of verb + ‘complement’)

Whilst our usual logic (such as we might use with prepositions in phrases like ‘给我买了礼物’) might be to group these 3 parts up into:

[把 + noun-phrase] + verb-phrase

i.e. [‘took the noun-phrase’] AND ‘did something with it’

the correct logical structure is actually:

把 + [noun-phrase + verb-phrase]

i.e. ‘把 such that [‘the noun-phrase does the verb-phrase’]’

with the post-把 noun-phrase being a kind of ‘mini-subject’ of the verb-phrase (= verb + ‘complement’) part. This interpretation of the internal structure of the 把-structure shows us why a sentence like ‘我要把他打断腿’ makes perfect sense in Chinese, even though it might initially feel like it goes against the way we have been taught to understand the meaning of 把. This is the reason why understanding the technical syntactic and semantic details of 把 does matter, or is at least useful – it helps us to understand what is and what isn’t a valid 把-sentence. And for us here, it shows us that it is possible for a 把-sentence to have causative meaning, a use of the 把-structure that is not well documented in pedagogical resources (so, think yourself lucky that you’re getting told about this here!).

Now that I’ve done my technical spiel, let’s look at some “causative 把-sentences”. In most of the examples we have seen so far, the causative interpretation is merely a way that we might look at a 把-sentence to help us understand its meaning. However, the REAL fun happens (did he just say fun? (why, yes, he sure did!)) when the subject causer is not actually a person or animate entity, but simply a ‘thing’. The resulting sentences sound really odd if we translate them too literally in English, but in Chinese they work when we interpret the presence of 把 as adding causative meaning to the sentence. So without further ado, welcome to the “Weird and Wonderful” Zoo of 把 (again I want to acknowledge The Syntax of Chinese by Huang et al. (2009) as the source of most of these wonderful examples):

这瓶酒把他醉倒了。 Literally: ‘This bottle of wine took him and was drunk to the point of falling over.’ Actual meaning: ‘He got drunk on this bottle of wine to the point of falling over.’

那三大碗酒把李四喝醉了。 Literally: ‘Those 3 bowls of alcohol drank Lisi until they were drunk.’ Actual meaning: ‘Lisi got drunk drinking those 3 bowls of alcohol.’

十首小曲把林一唱得口干舌燥。 Literally: ‘The 10 tunes sang Linyi until they were hoarse.’ Actual meaning: ‘Linyi sang those 10 tunes until he was hoarse.’

李四的笑话把林一急死了。 Literally: ‘Lisi’s joke worried Linyi to death.’ Actual meaning: ‘Linyi was worried to death by Lisi’s joke.’

这场排练把我们唱累了。 Literally: ‘This rehearsal sang us until it was tired.’ Actual meaning: ‘We sang ourselves tired during this rehearsal.’

你把我笑死了。 Literally: ‘You took me and laughed yourself to death.’ Actual meaning: ‘You made me laugh (myself) to death.’

这本书把我看得眼睛都累了。 Literally: ‘This book read me / looked at me until its eyes were tired.’ Actual meaning: ‘Reading this book made my eyes tired.’

You’ll notice with these sentences that you really have to think carefully about the theta-roles/θ-roles – which is the technical way of saying ‘think carefully about who does what’. Often, you will expect the subject of the sentence to be the person/thing doing the action, but then probably do a ‘double-take’ and realise it’s not. That’s what’s so curious about these kinds of 把-sentences to me – our normal expectations of the subject being the ‘do-er’ of the action and the object being the person/thing the action is done to are flipped, and it seems that at times the object is the ‘do-er’ and the subject is the ‘do-ee’ – yet they still make perfect sense in the Chinese-speaking universe!

Most of the time, the way to interpret these kinds of sentences will depend upon the specific verb in question, though an interesting point to be aware of is that it is still the post-把 noun-phrase that is affected in the examples above. We know this because if we change one of the examples such that it is implying that the subject is the one affected instead, the sentence doesn’t make sense e.g.

这本书把我看得眼睛都累了。 ‘Reading this book made my eyes tired.’ [Ok. ‘我’ is the one being ‘affected’ overall.]

**这本书把我看得封面都坏了。 Intended: ‘Me reading this book damaged its cover.’ [Not good. ‘这本书’ is the one being said to be ‘affected’.]

The technical explanation for this is that 把 doesn’t assign a theta-role to either the subject or the post-把 noun-phrase, as theta-roles come from the main verb of the sentence. It, however, does assign case to the post-把 noun-phrase [if that made literally no sense to you, I wouldn’t say it’s worth losing any sleep over].

Overall, my advice is to think of ‘causative 把’ in the following way:

- Some typical 把-sentences are best understood without thinking about ‘causative’ at all

- Some typical 把-sentences can be interpreted more easily if we think of there being an underlying ‘causative’ meaning

- Some 把-sentences are atypical in that they have a strong causative meaning that makes the sentence very hard to understand unless we bear it in mind

>> The 把-ability scale <<

Let’s take stock (stop! thief! somebody’s taking the stock!…okay, I’m done…). We’ve said we would think to use the 把-structure in the following situations:

- when we wish to/need to show that the object has been ‘changed’ in some way

- when we need an extra noun-phrase ‘slot’ in our sentence

- when we wish to show a ‘causative’ meaning

These rules-of-thumb will serve you well (if I don’t say so myself :D), but overall, we have to balance our knowledge of ‘the rules’ with the reality of language use “in the wild” – language is complicated, highly contextual and intuitions vary from speaker to speaker, as well as from context to context for the same speaker. Li & Thompson (1981), in their wisdom, observe that “speakers often disagree on their judgements of atypical ba sentences” and that “the same speaker may also make different judgements according to different contexts”. What this means is that 把-acceptability is thus a scalar variable, not something that can always be absolutely divided into ‘correct’ and ‘wrong’ 把-sentences. Our good friends Li & Thompson (1981) (on page 487, no less) provide us with a scale of the conditions under which 把 is likely to be used, when it is obligatory that it should be used and when it is not valid to use it. It goes a little something like this *cue music* (no prizes for realising that they don’t phrase it exactly in the way I have):

To add to this scale, 把-sentences often tend to be completed actions. However, remember that this is not absolute (or absolutely absolute?), and it is in fact possible to use 把 with ongoing situations e.g.

林一在把衣服包成一大包。 ‘Linyi is putting his clothes into a bundle.’

他正在把东西往屋里搬。 ‘He is currently moving (his) things into the house.’

and situations being stated in a more general way e.g.

你不把他仔细地审问,怎会查出问题。 ‘If you don’t question him carefully, how will you be able to find out the problems?’

Of course, because acceptability of sentences is a continuum, it probably shouldn’t be a surprise that the action being completed doesn’t always entail that 把 is okay e.g.

**他把这些文章看得很生气。

[The reason this one doesn’t work is that it’s simply stating how ‘他’ was feeling whilst doing the reading; it’s not actually that his anger changed what he was reading i.e. the essays in any way.]

6. 把 SUMMARY & AN EXERCISE

Whew! That was a long and very involved post! However, I’m pleased to say that I think this is pretty everything you would ever need to know about the 把-structure…EVER! Let’s do a quick summary of everything we’ve covered in this post:

- 把 is a preposition-verb-type thingy (a ‘light verb’)

- It usually shows a change in the object (not always physical, sometimes abstract), or a heightened sense of the object becoming ‘affected’ due to the action taking place

- 把 is usually used with action verbs, never with states (unless highly exaggerated), classificatory verbs, verbs of perception, or verbs that don’t actually ‘do’ something to the object

- If the verb is an exaggerated state verb, the change is usually in the subject

- The word order is:

subject + (adverbs) + 把 + object + (some adverbs) + verb + complement

though in super colloquial speech, where the meaning is not causative, the following is occasionally heard:

把 + object + subject + (adverbs) + verb + complement

- The object has to be definite in the context

- Using 它 ‘it’ as the object is fairly common in the 把-structure, even though 它 is not used much normally

- The subject is usually also definite

- The ‘complement’ must be included, which is usually one of the following – if in doubt, just use 了 & pray:

- destination or beneficiary [* note the word order is: verb + 在/给/etc. + (了) + place/person]

- duration or frequency

- result complement / directional complement

- complement of degree with 得

- reduplicated verb

- aspect marker (了、着 etc.) – if in doubt, use 了

- don’t use the particle 所

- 把 can be used to open up another noun-phrase ‘slot’ in the sentence; it is thus possible to use the pattern:

subject + (adverbs) + 把 + ‘affected’ object + (some adverbs)

+ verb + PART of the ‘affected’ object

- The 把-structure can also be used to show causative meaning i.e. that the subject causes a certain thing to happen to the object – when the subject causer is not a person, the sentence can sound quite weird in literal English, but is usually fine in Chinese

- 把-sentences often indicate completed actions, but not necessarily – (正)在把 is a completely valid language construct, as is use of 把 with somewhat more generic situations.

- The more ‘fringe’ our sentences get, the more native speaker opinion on their acceptability can differ. Well-formedness of 把-sentences is thus best thought of as a continuum.

Finally, just as a quick self-testing exercise, I’ve included a short task for you to have a go at. Below are 10 把-structure sentences. However, not all of them are correct or valid 把-sentences. Your task is to differentiate which are correct and which are not. For the ones which are not correct, see if you can say the reason why you believe it to be incorrect and then see if you can repair the sentence so that it’s correct. Enjoy!

Exercise:

To bǎ or not to bǎ?

That is the question

Correct or wrong? Why?

- 他把一朵花送给他女朋友。

老师把咖啡喝了一口。

- 我把他认识了。

- 妈妈把骂了一顿。

- 他把我们到宾馆。

- 我把他见了面。

- 他经常把老师当成同学。

- 他经常把一个老师当成同学。

- 小明把那些书都拿。

- 爸爸在桌子上把钱包放了。